Recent Articles

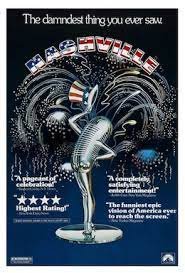

We Are The Story: Robert Altman Walks in NASHVILLE

This week, we complete our look back at Robert Altman’s work of the 1970’s with a deep dive into NASHVILLE, a sprawling panorama of the country music scene, of how we treat celebrity, of the intangible desire for change, of…well, practically everything, really.

As there must always be in every subculture across the Internet, there’s an ongoing discussion currently being held amongst the denizens of Film Twitter. This time around, it’s about the necessity of sex scenes in movies. I promise this is going somewhere.

Like many, I’ve been burned many a time by a sex scene popping up out of nowhere, usually when a parent or relative has just walked into the room (thanks, THE TERMINATOR!). And no doubt, there are many, many, many films and indeed entire genres that have sex scenes that exist only to (at best) titillate or (at worst) leer at a unsavory circumstance. However, I will mention that determining that kind of intent usually requires at least a little context, both onscreen and off, as well as some prior knowledge into the director’s prior work.

This is why a sincerely-held blanket “get rid of ‘em” philosophy gives me pause. Some are needed, some aren’t. And even if it’s not needed, I often think, who cares? Are jokes in film needed? Shouldn’t the characters stop being silly and just get to the point? But people joke in real life, so it becomes a movie thing. So it goes with sex.

As near as I can tell, a lot of the pushback on characters fucking is coming from intense old man voice Gen Z-ers on TikTok (Enjoy being blamed for everything for awhile, kiddos! We millennials had our turn). To some degree, then, this “discourse” can simply be chalked up to a lot of young people working out their feelings towards art, maybe for the first time, all against the backdrop of an increasingly complicated world. They’re just doing it on a never-ending public forum, something that a lot of us are extremely fortunate didn’t exist when we were in our teens and early twenties (a lot of my dog shit opinions are gone, nothing but so much internet dust now).

I also think the slow development over the past two decades of blockbusters becoming sexless, almost asexual, has pushed this topic to its boiling point. The FAST AND FURIOUS franchise serves as an almost too-perfect litmus test. Consider Dom and Letty, the defacto “main relationship” of the entire series (if you don’t count Tej and Roman), a couple that goes from grinding on each other in the first movie, 2001’s THE FAST AND THE FURIOUS, to barely touching by F9: THE FURIOUS SAGA. Whether this is a development of people being able to get their kicks and thrills for free from other media, or a consequence of film franchises now mostly being so many action figures being smashed together, I couldn’t quite tell you.

However (I’m arriving at “the point”!), others have identified a less obvious, but more consequential, source of sex scenes being considered by some as “unnecessary” to the plot of a given movie. It’s this: in a world where everything is “content”, anything that doesn’t move that “content” forward is thus anathema to enjoyment. In other words, the plot is now the thing. You can see this in action within, say, the MCU fan circles, where the multimedia franchise’s quickly-atrophying critical and popular acclaim over the past couple of years is getting explained away as the recent movies simply just “not moving the plot forward yet” (ignoring the fact that a few of them since AVENGERS: ENDGAME have just plain not been good movies).

This theory makes the most sense, at least to me. This mindset, if sincerely held by a significant amount of film fans (and in a world where exaggerating complaints to generate outrage, who knows if there’s truly a majority at play here), is a shame! On the one hand, yes, stories are what we ultimately go to the movies for. But stories come in so many forms, and can be told in so many different styles. A binary system of determining whether a story is “being moved forward” or not shields you from a bunch of different storytelling possibilities.

Case in point (see? “The point”! We’re here!), the story of 1975’s NASHVILLE is wide in scope and breadth, yet it’s told via tiny scenes that seems disconnected until they’re not. And often, the disconnect is sort of the point, too. Most scenes in it are explicitly not “moving the story forward” in a macro sense, yet when it’s all taken as a singular piece, not a single thread of the tapestry turns out to be out of place.

It’s an ambitious film, and one that is regularly considered Robert Altman’s magnum opus. Without having seen the entirety of his filmography, I’m still willing to go along with that, if only because of its wild confidence. There are so many characters and so many overlapping developments and movements that you’d expect it to collapse under its own weight, were it not for Altman’s light touch and almost audacious assurance.

More than anything, NASHVILLE shows that stories can be told any number of ways and be just as impactful in its totality than almost any film being made in the modern market. And that makes it worth a watch no matter who you are.

NASHVILLE (1975)

Directed by: Robert Altman

Starring: too many to count

Written by: Joan Tewkesbury

Released: June 11, 1975

Length: 160 minutes

What is NASHVILLE about? Well, there’s a short answer, and there’s a long answer.

In short, the film provides a snapshot (or maybe a panorama) of the beating heart of the titular city’s music industry, at least as it stood in the mid-seventies. A bevy of singer/songwriters and producers, some well-established, some who are aspiring, and some who have had better days, descend upon the Tennessee town in advance of an upcoming concert/fundraiser for Hal Walker, a rousing underdog Presidential candidate for the fictional Replacement Party (a candidate we hear a lot from but, tellingly, never actually see).

In long, though, it’s almost impossible to really illustrate what it’s “about” at first watch-through. The sheer scope of everything you see, of the criss-crossing storylines, of the absolute volume of characters at work here, and the way many of them disappear from the film juuuuust long enough to make you think maybe they’re not coming back, just in time for them to get a showcase scene….it’s probably best to just take it in the first time.

Oh, and NASHVILLE is also a de-facto musical, and one of significant heft. By someone else’s count, there’s about an hour’s worth of music (about a third of the film’s runtime), but it truly feels like a constant throughout. Infamously, many of the key songs (including the Oscar-winning “I’m Easy”) were written by the actors who sang them, something that apparently rubbed actual contemporary Nashville musicians the wrong way at the time. A fascinating New York Times article details the community’s reactions to the movie’s premiere in the real-life Nashville. There weren’t any riots or anything, but honest-to-god country superstars like Loretta Lynn seemed a little riled that actual country music artists weren’t used to develop the music.

Most of the time, I’d be on their side; a lot of the creative work (and the expertise to be found among it) has slowly been slid onto the plate of the onscreen performer, to the point that it seems most people assume everything is now improvised on set (seriously, fire up an episode of the OFFICE LADIES podcast sometime; 85% of the questions they get are some variation of “was [insert line or moment] improvised????”)

But, here’s the thing. I actually didn’t know the actors mostly wrote the music going in, and was a little shocked to learn it as a fact. It just all sounded like mostly legitimate country and bluegrass to my untrained ear. So, my sincere props, y’all! The New York Times article talks about how many of the lyrics were met by the country insiders in the audience with smirking recognition, perhaps indicating a level of parody at play here that mostly flew over my head. I just thought the music was actually good!

Another reason country stars, and thus Nashville proper, didn’t warm up to the film right away was this uneasy sense that they were being made fun of. After all, what is there to make of these exaggerated characters representing your home turf? Rumors also swirled that some of the major characters were one-to-one stand-ins for major current country stars which is, uhhhh somewhat true, actually; for instance, Barbara Jean is based on the aforementioned Lynn, Tom Frank (Keith Carradine) is based on Kris Kristofferson. Some characters were merely composites; Connie White (Karen Black) is a mix of Tammy Wynette, Dolly Parton and Lynn Anderson, while Haven Hamilton (Henry Gibson) is a cross between Porter Wagoner, Roy Acuff and Hank Snow.

Naturally, Altman had always resisted this literal interpretation. To hear it from him, NASHVILLE is, if anything, a movie about Hollywood. This narrative framework was just set in Nashville mainly because of his growing affinity for the area. Although the film was mostly improvised on set, the standard modus operandi for Altman by this point, Joan Tewkesbury had provided the road map, filling up a diary of her notes, experiences and observations. Some of them made it directly from her pages to his film, most notably the freeway pile-up that begins crashing the characters together.

But the actual tapestry of NASHVILLE? The ecosystem of country music and the eccentrics that it attracts, all amidst this feeling of unseen, intangible hope, could just as easily be applied to the film scene in California. Or the theater scene in New York. Or a million other subcultures in this strange, bizarre, wonderful world we live in. Anyone who’s found a community through passion can recognize the archetypes at play; the fallen star, the up-and-comer, the knowing cad, the overzealous fan, the service man who wants to climb the ladder.

More to the point, NASHVILLE is so clearly about the American experience, both in broad and specific terms. It is both intensely of its time, yet unbelievably timeless. Hell, many of the key creatives behind this might be shocked (or appalled) at how relevant it all still is.

NASHVILLE is very much captured in 1975, in particular when considering how much shit had gone down in America the previous fifteen or so years. JFK, MLK, Malcolm X and RFK’s assassinations had all been in the past twelve years (something that is so clearly on this movie’s mind; more on that in a second), and the Watergate scandal earlier in the 70’s had done much to erode what was left of the population’s confidence in its government after the prolonged war in Vietnam.

A strong desire for change was in the air, although if NASHVILLE is to be taken at face value, there was skepticism that it was really going to be possible, at least not without a fight. As mentioned, Hal Walker, the reason the story of the movie is even happening, the speaker of many amazing and rousing platitudes….dramatically speaking, he’s a ghost. We never see him, his words just sort of float through the atmosphere. Everyone gathers for the mere possibility of change, even if we don’t know what it looks like.

A lot of NASHVILLE’s thesis statement can be gleaned from its pretty glorious opening scene, two songs being sung in completely different styles, recorded in completely different contexts, and sung by people of completely different races. One half of the scene is Hamilton attempting to record a very straight-laced and traditional Bicentennial song, a literally-titled “200 Years” (written by Hamlin and Richard Baskin). Its chorus refrains, proudly if a little naively “we must be doing something right to last 200 years!” It’s rousing, if staid to its core.

The other half, in another room within the same recording studio, is Linnea Reese (Lily Tomlin) and the all-black Jubilee Singers (from Fisk University, at the very least based off a very real choral group, although I couldn’t confirm if they were appearing as themselves here) laying down a rousing gospel track. As the piano joyously pounds, Linnea struggles to be heard over the voluminous sound behind her, asking over and over if we believe in Jesus.

Two completely different and unique styles, borne from diametrically opposed lived experiences and perspectives, living right next door to each other. That’s Nashville. That’s America.

******

It’s difficult to figure out exactly who to best highlight amongst NASHVILLE’s cast. There are so many moving pieces within its ensemble cast that you could probably watch the movie ten times and have a new favorite every single time. However, I’ll highlight a couple that took me by surprise.

Like many comedians from the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s, I was primarily familiar with Lily Tomlin from her hosting stints on Saturday Night Live, although most people at the time probably knew her from ROWAN AND MARTIN’S LAUGH-IN. Folks nowadays likely know her from stuff like GRACE AND FRANKIE, a comedienne from previous generations that thankfully appears to be accepted and loved by younger generations (also known as the Catherine O’Hara Club). I hadn’t really ever seen her do a non-comedic role, however, although I had little doubt she’d be great.

She comes through! I think what really surprised me and made her stand out is that Linnea is so normal compared to both everyone else in the dang movie as well as every other character I’ve seen Tomlin play. She’s heartbreaking in her simplicity and nobility, a gospel singer that takes care of her two blind daughters, all the while being left unsatisfied by her husband (more on him in a second!). When she gets the chance to sleep with Tom, she can’t resist.

Linnea could be a really difficult character to sell to an audience, but Altman or somebody must have known that we were going to love her because she’s Lily Tomlin. They were right. One of the most unforgettable and memorable moments of NASHVILLE’s entire 160 minutes is her staring silently at Tom singing her “I’m Easy”. Maybe she knows she’s making a mistake, maybe not. All she knows is she’s doing something for her. She does all of us without a single written line of dialogue. I’m convinced she’s why the song won an Oscar.

If there’s a main backbone to the film, it’s probably the story of Barbara Jean’s recovery from a nervous breakdown. Ronee Blakely plays half of her scenes laid up in a wheelchair, but I found her entire arc pretty engaging, if only because it reminded me so much of how celebrities, especially women, tend to get squeezed from all ends until they collapse, sometimes emotionally and sometimes literally. Every aspect of her arc here happens publicly; her return, her collapse, her heartbreaking failed performance at Opryland (a scene so beautifully acted by Blakely, by the way, that I felt like I was watching a concert doc, not a narrative film), her violent death.

About the only thing she gets to do in private is recuperate. Even then, she gets to watch from her wheelchair as more glamorous performers take her now vacant slots, and she gets to observe her well-meaning manager/husband Barnett dismiss her anxieties as the beginnings of another nervous break. She never catches a break once in the film, but that’s how it goes for female celebrities throughout the past, present and future. We feel for them only when they’re finally at rest.

Barbara Baxley, star of both stage and screen, provided one of the other most memorable moments of the movie for me as Lady Pearl, the wife of Haven Hamilton. Midway through NASHVILLE, she gives this speech to Opal, a British reporter and our de-facto audience surrogate. Within this monologue, she talks about the reach John F. Kennedy Jr. had on areas of the country not previously thought possible, his subsequent assassination and. In doing so, she verbalizes and dramatizes the deep national tension at the time (and was still very much lingering in 1975) that NASHVILLE taps into so well:

And then comes Bobby. Oh, I worked for him […] he was a beautiful man. He was not much like John, you know. He was more puny-like. But all the time I was workin' for him, I was just so scared - inside, you know, just scared.

It’s here that the film starts to contextualize its ending. More on that in a second.

Finally, was there some sort of presidential order signed that mandated Ned Beatty appear in every single great American 70’s movie? This marks his third appearance on this blog in just under a year (including NETWORK and MIKEY AND NICKY). And, no surprise, he’s fucking great. You’re never going to believe it, but he plays an unsavory lush in this, although it’s notable that he never really does anything unsavory. He’s just not there for this saint of a woman he’s lucky enough to share a roof with. I’m a little shocked that Beatty only worked with Altman one more time (1999’s COOKIE’S FORTUNE). He’s a natural for the expository nature of his film set.

I could go on and on and on about every single character, and a real legitimate breakdown of this movie would almost have to in order to really dive into every nuance. You’d have to because these characters are the story. They are the plot, and the plot is them. Their human decisions affect the decisions of others. Or they don’t. Maybe their stories are purely internal. But that’s the story of humanity.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t talk about the ending, and why it’s so powerful in the midst of a world where just stepping outside can feel fraught with peril, where scanning the news invites you into a nightmarish hall of mirrors. In NASHVILLE’s final scene, as we finally reach the Hal Walker fundraiser, Barbara Jean gets assassinated on stage by a quiet, seething fan (a moment that seems eerily prophetic in the aftermath of Christina Grimmie’s 2017 murder, resulting in a world where stars like Taylor Swift have to walk around with what is essentially human Fix-a-Flat), and her limp body is immediately (albeit slowly) taken off the stage.

Amidst the shock, however, the indomitable human spirit endures. A new star takes the stage, and Hamilton urges the crowd to not give up, chillingly stating “we’re not Dallas!”. The entire crowd takes up in song.

It’s both ghoulish, bizarre yet simply moving. It’s America.

Although there is an uncharitable interpretation to be made of these final moments (a prediction of our current “the show must go on” culture that has essentially rotted our brains), I took it as perversely positive. For everything that this fucking country has had happen to it (and, of course, what it’s unleashed on others, both within and beyond its borders), we have a knack for moving forward anyway. Concerts endure. Sporting events endure. Beyond all reason, we still find political candidates to rally behind. We just kind of keep going.

Just, you know, try not to get too much blood on you while you do it.

*******

Not that it ultimately really matters, but Altman seemed to find his juice at the Academy Awards again after the success of M*A*S*H had thus far eluded him in the early to mid 70’s. NASHVILLE was nominated for five Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director. It lost both of those, although it must be said that this particular Oscar race was incredibly stacked. Its competition for Best Picture:

ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST (eventually won)

BARRY LYNDON

JAWS

DOG DAY AFTERNOON

Altman’s competition for Best Director:

Milos Forman (CUCKOO’S NEST, and eventual winner)

Federico Fellini (AMARCORD)

Stanley Kubrick (BARRY LYNDON)

Sidney Lumet (DOG DAY AFTERNOON)

What are ya gonna do? Altman had to settle for it being considered his magnum opus almost immediately, and probably his most enduring and popular film, besides maybe something like the aforementioned M*A*S*H*. Oh, and it still holds the record for most Golden Globe nominations for a single film, even all these years later. Not bad!

This brings me back to the “discourse” at the beginning of this article. By the same metric of “not ostensibly plot related = wasted calories” that leads to the very existence of sex scenes being questioned, NASHVILLE fails any possible equation you could run it through. Yet, do you want to live in a world where a movie like it could possibly be considered bad storytelling by any measurement?

Almost fifty years later, NASHVILLE remains an astounding achievement, both in scope and scale. It manages to reflect how stories can come from anywhere and everywhere. They surround us, both small and large. They are us. And there’s no “right way” to tell them. Let movies indulge! Let them take their time! Let them take you down oddball paths! The best ones have a way of enduring even when they’re weird.

That’s America.

FOUR WEEKS OF MAY: MIKEY AND NICKY

Elaine May’s third feature is a quiet character-driven masterpiece, despite all the chaos behind the scenes that ran May from the director’s chair for another decade.

My “film journey”, for lack of a less pretentious term, started relatively late in comparison to others in my circles. In fact, I’d argue that it only really got going in earnest a couple of years ago.

Of course, I’ve been watching movies my whole life. When I was a kid, my mom showed me the big works of Disney, Spielberg and Lucas as well as select viewings of Classic Hollywood and pre-code stuff. My grandma opened me up to the comedic charms of the Marx Brothers, Abbott and Costello and the Three Stooges. Between me and my collection of friends, we covered most of the major blockbusters and Oscars bait that the late 90’s and early-mid 2000’s could offer.

But I’m not sure that I really dug into movies as something serious to study until the very recent past. True, I devoured trade magazines like Entertainment Weekly, and dutifully watched Roger Ebert and the villainous Richard Roeper every Sunday night. But this was really more of a way to stay on top of what was coming out, and what movies seemed to be trending upwards or downwards. It wasn’t a way to check out what had come before, or even analyze why I liked what I liked. It was just knowledge, nothing more.

There were several reasons for this paucity of actual viewing experiences. One of them was that watching the classics could be difficult, especially if it was a foreign film, as it often necessitated a trip to the video store and hoping for the best (Netflix’s “DVD by mail” service helped immensely in this regard). The primary reason, however, was that I went through a prolonged “anti-pretension” phase that kicked in around mid-high school and extended itself through, I dunno, like my early thirties or something.

It basically went like this: For the first third of my life, I hesitated to really dig into something that I knew was a passion of mine, lest I come off as a smart-ass know-it-all like the rest of the smart-ass know-it-alls I knew. Of course, this failed to account for the fact that this kind of “fuck the elitists” posturing was itself a form of pretension, the belief that your opinions were simply better than everyone else’s (this also leads very easily into living your life as just the devil’s advocate. People like this thing? It must be shit. I like something? It must be an underrated masterpiece, even if the thing I’m talking about is Spider-Man 2).

Anyway, by the time I hit 30, it dawned on me that, as a result of this kind of time-wasting, there were a lot of classics I just hadn’t seen. There’s still an embarrassingly long list. Even worse, a lot of the friends I have now are very smart film buffs that I just couldn’t follow along with or add to in conversation, the result of years of burrowing into my already-established interests, rather than expanding them.

To make matters even more devastating, I had discovered the much-beloved, now-defunct streaming app Filmstruck much too late, essentially after it had already been discontinued by Warner Media. Here it was, a streaming site that had put selections from the Criterion Collection and Turner Classic Movies potentially at my fingertips for a couple of years and I squandered it, completely unaware it was an option until it was already gone. It’s a terrible thing to find out about retroactively. An easy-to-access doorway to film history and I had blown it.

Enter The Criterion Channel.

For the unfamiliar, it’s what it sounds like: a streaming channel curated by the people behind the Criterion Collection, a pseudo-successor to Filmstruck. At the beginning of 2019, the launch of the app was announced, and an advance mailing list was opened up to the curious. As a lead-up to the app’s launch, a Movie of the Week program was announced. This way, potential subscribers could enjoy a single movie on the prototype platform, typically a movie that would give one an idea of the kind of programming the Criterion Channel would eventually house. I eagerly signed up, not wanting to miss another opportunity. This way, at least it seemed to me, I could start my film education in earnest, one week at a time.

First movie up? MIKEY AND NICKY.

It’s fair to say, then, that this week’s movie is responsible for my curiosity being stoked, and is responsible for the last few years of articles. Feels relevant, then, to revisit it again now for Elaine May Month.

Let’s get started.

MIKEY AND NICKY

Directed by: Elaine May

Starring: Peter Falk, John Cassavetes, Ned Beatty, Rose Arrick, Joyce van Patten

Written by: Elaine May

Released: December 21, 1976

Length: 106 minutes

MIKEY AND NICKY is a fairly simple movie, at least on its face. John Cassavetes is Nicky, a paranoid man holed up in an apartment for reasons that are initially only alluded to, although it seems as if the recent murder of a bookie might have something to do with it. Peter Falk is Mikey, Nicky’s lifetime friend who comes to his aid (not for the first time, it turns out) and just seems exhausted. His relationship with Nicky seems to swing between that of an older brother and of a father. At the beginning of the movie, he force-feeds him medicine; near the end of it, he’s fighting him in the street.

The above premise leads us into that most satisfying of movie genres, that of the night-time odyssey through the streets of a major city, in this case, Philadelphia. Nicky, fearing for his life, wants to constantly be on the move, while Mikey seems most concerned about keeping themselves in one place for reasons that are initially ambiguous. All the while, they appear to be followed by a gangster, played by 70’s perennial Ned Beatty.

MIKEY AND NICKY presents itself as a two-character play for the most part. As they bob and weave from one place to another, we get to see a lot of conversations between our two titular characters. As a result, we gain a ton of insight, implied or otherwise, as to the relationship between the two of them, as well as their own individual lives.

And, boy, do we have two great leads to present this tandem.

I want to first dig into Cassavetes’ work as Nicky. John Cassavetes is known more as an influential independent director now that it’s all said and done, but his career started as an actor. His appearance in MIKEY AND NICKY is interesting to me since the movie itself feels so influenced by Cassavetes’ directorial work; so much of it is close, intimate and honest.

Cassavetes’ Nicky is all tics and neuroses, befitting a man who feels like every moment could be his last. He’s obviously not taking care of himself and has a penchant for rash and impulsive actions, which is why he’s found himself in trouble in the first place. He refuses to do anything to take care of the ulcer he’s obviously suffering from. And most of all, he’s unspokenly suspicious of his only friend (as it turns out, rightly). Cassavetes has a lovely, natural chemistry with Falk, no doubt the result of years of collaboration together.

Peter Falk is yet another one of those guys that I think we all know, but maybe don’t appreciate to the fullest. I’m ashamed to say it, but I’m actually not that familiar with his most famous role, that of Columbo. But I have become increasingly more acquainted with Cassavetes. But, man, is there an emotion that face, that so unique face, couldn’t so subtly register and embody? In a movie that’s all about what’s not being said (like jazz, man), Falk’s portrayal of Mikey is the audience’s emotional Cliff Notes. You are keenly aware of his overlying (and often conflicting) feelings: guilt, exhaustion, genuine brotherly affection, anxiety….it’s all there. I don’t know that the movie would have worked without him.

Both Falk and Cassavetes complement each other’s performances so well. Nicky comes off as so sufficiently tiresome that Mikey’s frustration and exhaustion with a lifetime of being maybe his only friend feels justified and obvious. His eventual betrayal also feels emotionally true, and Nicky slowly sussing out how the night is destined to end without ever truly explicitly confronting Mikey about it is ultimately where MIKEY AND NICKY derives its power.

(May I say how much I like mob movies that are almost exclusively about the lowest rungs on the org chart? So many are about making your way to the top. However, MIKEY AND NICKY there’s much drama to be wrung from the people that are frankly fortunate to even be at the bottom.)

The production of MIKEY AND NICKY was the one that appeared to run May away from the director’s chair for over a decade. Filmed in 1973, the movie wouldn’t be released until 1976, so long and how tense the conflict was between her and Paramount Pictures, her old foes from A NEW LEAF.

Again, May’s budget ballooned quickly; when the movie was being produced by Twentieth Century-Fox, the budget went from $1.6 mill to $2.2, which caused the studio to drop the film entirely, allowing Paramount to swoop in to save the day. Paramount’s involvement came with stipulations, the most vital of which were the $1.8 million budget and the hard deadline of June 1, 1974 for the film to be completed. Well, 6/1/74 came and went, and no completed movie was delivered, although the budget had inflated to almost $4.5 mill.

Part of the extended production had to do with May’s decision to constantly keep the camera rolling, maybe for hours at a time if she deemed it necessary, even when Falk and Cassavetes had long since left the scene (as the famous story goes, a new camera operator got in trouble for calling “cut”; when asked why in the world the take should continue after the actors left the physical set, May replied, “because they might come back”). As a result of this unusual decision, the film has this completely improvisational feel to it, even though it indeed was pretty much entirely scripted all the way through.

I’ve always had mixed feelings about this approach. On the one hand, it does feel wasteful, and I can’t help but understand why Paramount was having a panic attack regarding all this. I also don’t quite understand the point of continuing to roll the camera at the end of the scene if you’re following along with a tight script. Except to say that, as mentioned, MIKEY AND NICKY has this sprawling feel as a result. Even though the film is only 106 minutes, it feels, in the best way possible, like you’re with these two characters the entire twelve or so hours that the story unfolds during. You’ve been through a marathon evening, and I don’t know if the movie would have had the same effect if a more efficient director (say, Clint Eastwood) had directed it. We’ll never know.

Anyway, Paramount took Elaine May to court. Having flashbacks to how everything regarding A NEW LEAF went down, May was determined to not let the same studio butcher two of her movie. She took the extraordinary measure of essentially holding two reels of the movie hostage, storing them in a garage in Connecticut that belonged to a friend of her husband’s. She eventually relented and allowed Paramount to create the final cut, although the experience was devastating enough that she wouldn’t return to the director’s chair for another ten years.

Maybe all of this was the sacrifice needed to make MIKEY AND NICKY what it was. Because interestingly, although I ultimately don’t think it hangs together quite as well as THE HEARTBREAK KID, I think if I had to recommend just one Elaine May film, it would be this one. It illustrates so well the disruptor spirit that May retains to this day. She made a masterpiece by doing it her way, even though her way led her into a courtroom once again, and her treating a random suburban garage like it was WACO or something.

And, more importantly to me, this version of MIKEY AND NICKY ultimately led me to this moment right here, turning this space where I was awkwardly reviewing episodes of SNL or whatever to a space to talk about movies and why they work. It was a joy to run down the streets of Philadelphia again. Do yourself a favor and do the same sometime this week, too.

Best of

Top Bags of 2019

This is a brief description of your featured post.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Sign up with your email address to receive news and updates.